BY DR. A. L. DALLI (Ph.D) Updated and Abridged by BACHAMA TRADITIONAL COUNCIL, NUMAN.

(updated & complete)

The early history of Adamawa where the Bachama live is not yet fully known. It is generally accepted that none of the present inhabitants of the area are autochthonous (Kirk-Greene, A.A.M. 1969:15 Dalli, A. L. 1988:62).3 The Adamawa area has witnessed successive waves of invasion by the Jukum, chamba and Batta during the 17th and 18th centuries. The last wave of these invasions was the Fulani Jihad, which occurred at the beginning of the 19th century, resulting in the division of the former Adamawa Province into three parts: Adamawa Emirate to the North and East, Muri Emirate to the South and West, and sandwiched between the two Emirates is a block of unconquered minority ethnic groups, who, in the Numan area include the Bachama, Batta, Mbula, Kanakuru, Lunguda, Pire, etc.

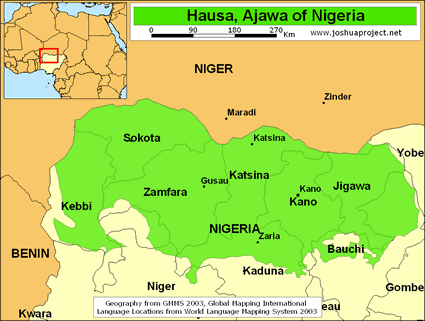

All these ethnic groups in the colonial literature enjoyed a fierce and warlike reputation. The Batta and Bachama People The Batta and Bachama people are sub-groups of a single tribe as mentioned above. The Batta were the predominant people of Adamawa in the days prior to the Jihad of 1804. Batta or appropriately Bwatiye or Pwatiye, denotes the people of God, or the people from above. The Jihad broke and scattered them in many directions, the main body retreating south and west by stages, until they reached the vicinity of Demsa Mosu. Here, according to oral tradition, the group split into two following an intrigue by the younger twin, Zaro Dembune against his elder twin brother Zaro Kpalame, who occupied the throne. The group which seceded under Zaro Dembune crossed the Benue River at Nzomwadiksa and established the Bachama Chiefdom (Dalli, A.L. 1988:9, 66-72). The word Bachama was never meant for a tribe. The seceding twin used it as an expression to refer to the manner in which he intended to establish a kingdom and build a followership to counteract the forces of hostile ethnic groups in the vicinity. The expression “Bachama” became synonymous with the settlement, which became the headquarters of the Chief. The Fulani referred to this settlement ‘Lamorde’, meaning capital or seat of the ruler (Carnochan, 1967; a: 622).5 The Sokoto Origin of Batta and Bachama People The tradition of origin linking the Batta and Bachama to Sokoto or Gobir has generated lots of controversy in the literature.6 But by way of explanation, one could add here that the royal families of Demsa and Bachama hold this tradition together with some non-royal clans that accompanied the chieftaincy at the period of the secession. The tradition does not impose itself on all the Batta and Bachama people, nor does it claim that the Batta and Bachama people are homogenous. Most non-royal clans have divergent traditions of origin and how they became associated with the chieftaincy. At any rate, Kabe (non-royal clans) are the custodians of Bachama sacred tradition, as well as of rituals and the chieftaincy. Zomye (royal clans) are eligible to the office of the chief. A Bachama chief takes charge, upon appointment, of the economic exploitation of the natural environment. The political history of the Bachama chiefdom lends credence to the conquest theory of state in which an invading group with the chieftaincy assimilated an autochthonous group with the local environmental knowledge. As time went on, the leaders of the Bachama migrations we deified but their priests were drawn from the autochthonous group.

The Bachama Traditional, Political and Administrative System

The chieftaincy (homne) in Bachama society is the highest decision making body both in the political and religious institutions as well as in the land tenure system.

Moreover, the chief (homun) presides over the cults and gifts to the gods must emanate from him. A number of stages in the installation of Bachama chiefs are discussed here to emphasize that a chief should be duly elected before assuming office. Furthermore, the discussion of the traditional political administrative system centers on the interaction of four major agents of political control that I consider important and which relate to the topic of this write-up. These four agents of political control in Bachama society are Zomye (royal clans), Kabe (non-royal clans), Homun (King), and the administrative council of elders in Lamurde and the outlying villages.

(I). Zomye (Royal Clans)

There are six Zomye clans: Kowo, Magbullaron, Nomupo, Nokodomun, Waduku and Impang. All claim descent from Zaro Dembune, also known as Matiyavune; Founder of the hut and first King of Bachama, the settlement that was restyled Lamurde. In theory, all adult males from any of these royal clans are eligible for appointments to the office of the King where there is a vacancy; but in practice, only wealthy candidates from these clans can vie with one another for that office. Traditionally, wealthy people in Bachama society were those with many wives and children, granaries of sorghum and several heads of livestock. In the traditional economy, wealth was concentrated in the hands of Bachama elders. They monopolized the chieftaincy and operated a gerontocracy.

This monopoly was only broken when the Bachama economy became monetized following the advent of colonial rule. Young men from these royal clans vied for the chieftaincy with success. In 1921, for example, Mbi (Gorosobwe), who was known to be vying for the chieftaincy, despite the fact that there was an incumbent chief on the throne, escaped to the missionaries in Numan so that Kpafrato could not deal with him. However, when Kpafrato was deposed by the colonial government, Mbi was ‘elected’ Chief of Bachama through popular vote defeating the favourite candidate Mbuldi. The latter was well known to the colonial administration and was thought to be the likely choice of the Bachama. Mbi was a school teacher in Numan and was the first Christian Chief of the Bachama.

At any rate prospective candidates buy the chieftaincy, this is known as do homne (buying the chieftaincy). They offer gifts secretly and on the continual basis to the non-royal clans (Kabe) in Lamurde as well as to Jeke in Hadiyo. Unsuccessful candidates can demand the return of their gifts, although most of them do not because their children or other close agnates might be interested in vying for the office of the chief in another generation.

Rivalries for the office of the chief, following the death of an incumbent, have in the past led to bloodshed between some of the royal clans. In the pre-colonial period, political conflicts among the Bachama were resolved through military might. Even when the new chief has assumed office, candidates suspected to be vying for the office of the incumbent chief were banished for life from Bachamaland.

(ii). Kabe (Non-Royal Clans)

Kabe are the custodians of the chieftaincy institution, religious rituals and sacred history of the Bachama people: They have the following ritual objects in their custody: Mosuto (Sacred rain pot), Kofyi wato (sacred spears), lyeni wato (elephant tusk horns), jindo wato (royal horse’s tail) and Ramo Ngbakowon (The golden stool). Thus Kabe are the de facto as well as de jure natural museums of Bachama cultural objects. Furthermore, Kabe are the traditional occupants of Lamurde, the Bachama capital; Zomye live elsewhere throughout Bachamaland and only move to the capital during the tenure in office of their clan. They vacate the capital when their chief is no longer in office.

Zomye and Kabe titled elders hold important offices in the chief’s administration, both at the headquarters and in the outlying villages. The kingmakers’ patriclan Jeke (s. Zeke) live in Hadiyo, about 2.2km southeast of Lamurde. They form a patriclan village and receive recommendations on each candidate vying for the office of Hama Bachama from Kabe elders in Lamurde, and have the final say in the selection procedure. Similarly, when a chief is deceased (ha ya), Jeke perform important function in his burial (Dalli, A.L 1988:113). Bachama Kings are buried in ndoko hidon (the lone hut) in Lamurde, elderly Zomye are buried in Venti beyin; titled Zomye are buried in ndoko zomon while kabe elders are buried by fellow kabe in the compounds.

(iii). Homun (Chief)

When there is vacancy, Kabe select a new chief from one of the six royal clans (Zomye). Theoretically this should be in rotation so that each clan could take turns in providing chiefs. In practice, a few clans have monopolized the chieftaincy at the expense of others. There are a number of stages in the installation ceremony through which the chief elect must pass to be considered duly elected before he takes possession of the palace (voti). It is generally held that if any of these stages is missed out, the gods would be angry and the chief might die.

(a). Fara Borongti is the first stage in the installation ceremony. Jeke tie the waist of the chief-elect with a grass rope (sunga shafa) and lead him into the shrine of Fara Borongti in Lamurde. Inside the shrine the chief-elect attempts several times to sit on a sacred stone but is restrained on each occasion by the priest in charge until he eventually succeeds.

(b). Ndoko Peken (“room of the broom”) Jeke arrive within the vicinity of the shrine of Ndoko Peken still holding the chief-elect by the rope tied to his waist. Here they are met by the priest, Homo Peke. He stops them and presents a white strip of cloth in place of the grass rope. Jeke untie the rope and give it to Homo Peke and the latter ties it on a stone.

(c). Ndoko Gbidan (“the open space of the spirits”)

At this stage, Jeke and the chief-elect meet three important kabe titleholders; Nzopwato, Ndyewodyi Gongrong and Nzofame. The leader of the Jeke, known as Zeke, hands over the chief-elect to Nzopwato and goes back to Hadiyo, his village. If there is no ill-feeling against the chief-elect from Jeke. But, should there be feelings of ill-will against the chief –elect or his patriclan, then Nzopwato is compensated at this or else the remaining stages are suspended.

At Ndoko Gbidan, Ndyewodyi Gongrong presents the chief-elect with the official walking stick (staff), (Garatoa Matiyavune) and Nzofame gives him the traditional shield of Matiyavune (Kurmoto) as well as the spears of Matiyavune (Kofe da Matiyavune).

(d). Kwashafe is an open meeting ground, where the chief-elect attempts to take some soil but is dissuaded by Nzopwato. After several attempts he succeeds and takes the soil. It is customary among the Bachama to take fresh soil from the shrine of the gods and sprinkle it on both shoulders as a symbol of submission. The chief-elect, in taking the soil, submits himself to the will of the gods.

(e). Hakabong: The first day of the installation ceremony ends here at Hakabong. Nzopwato hands over the chief-elect to Ndyewodyi Kowo and the strip of cloth is also removed from his waist, he puts on garments and sits on mats arranged in a shelter (kwakra). The chief-elect receive visitors and a cow is slaughtered to provide meat for the people. He sleeps that night at Hakabong.

SECOND DAY OF THE INSTALLATION

The chief-elect sits on the mat facing the East, and Jeke arrive from Hadiyo. They line-up facing him. The eldest of the Jeke moves forward and lifts the chief-elect and points to the East and West announcing the boundaries of his jurisdiction with the words, all that is your land as from today. Zeke returns on the long line of Jeke. They turn to the East and begin to clap their hands in a gentle manner, as one of them recites their sacred speech which is inaudible to other listeners. The recitation lasts for over one hour and marks the end of the formal installation which the public may witness. Jeke are later served the meat of the slaughtered cow.

(f). Gongrong

At about three o’clock in the afternoon, a horse is brought on which the chief-elect rides towards the stream known as Gongrong for a royal bath. On the way he is stopped at Madon (a ward in Lamurde) and asked his chieftaincy names. He is expected to give two names; for example, the present Hama Bachama gave the names Goro Ngakye (a pool of hooks) and Kuzo-Vudeto (mat of the courtyard). Having identified himself, Ndyewodyi Gongrong and Kpa Duwe escort the chief-elect to Farang where he is bathed by the former. Unauthorized spectators are barred from accompanying the chief-elect.

(g). Yedikwaton (bitter stomach)

The chief-elect is brought back to Lamurde (the golden stool) is kept. But before going into the shrine, he is again asked his chieftaincy names after which he dismounts the horse and Ndyewodyi Gongrong leads it away.

Ndyewodyi Ngbakowon takes the chief-elect on foot into the shrine where he is questioned on a number of issues. He later gives a ram to be sacrificed to the shrine. At Ngbakawon, a curios rite is performed. A monitor lizard (bwalato) is brought with its forelegs tied behind its back, the same way prisoners are tied. People then jokingly address the lizard saying, yes you were not all that you should have been; in bygone days you even ran after the chief’s wife. The lizard is then taken to the royal graveyard and released. The explanation advanced for this ritual is that the new chief must not use his power to crush old enemies; therefore all past grudges must be laid aside. In former times, the chief-elect sometimes remain at the shrine for fifteen days to complete the rite de passage required for his new office. As recorded my Meek, C.K. (1931b3) the monitor lizard must be obtained for this ritual, or it is considered the chieftaincy is not ripe.

When the period of seclusion is over, the chief takes possession of his Palace (Voti) by stepping over the carcass of a slaughtered cow at the entrance. Two explanations are given for this action: First, that the chief left behind all conduct which might be inconsistent with his new office; second, that the slain cow has secured the palace from invasion by the spirit of the former chief. After this ritual, a crown known as Palwalato is placed on his head.

This consists of strips of brass worn round a red fez, with a band of white cloth surrounding the forehead. A few ostrich plumes protrude on the sides. The crown is worn on public occasions such as festivals and some religious rituals, which require the presence of Hama Bachama. Bachama chiefs are never turbaned.

The rituals surrounding the installation ceremony of a Bachama king have symbolic significance. First, the chief-elect is publicly humiliated and is tied with a grass rope at the waist like a prisoner, and led away without a garment. This is meant to break down his pride because Bachama chiefs are captured and given the mandate to rule their subjects.

Second, he is presented the official walking stick (staff), the shield and spears of Matiyavune, the first Bachama King at Lamurde. These symbolize continuity; the walking stick is brought out during ceremonies while the shield and spears signify license to militarily defend the territorial boundaries of Bachamaland. Furthermore, the chief-elect sprinkles sand three times on his shoulders in submission to the will of the gods; he takes chieftaincy names, and is given a royal bath, after which he licks a scratched spot to ‘cool’ his heart. Here we have the rebirth of a new personality. Then the chief-elect is secluded inside the shrine of Ramo Ngbakowon, which contains the golden stool; the soul of the Bachama people. From here he emerges to take possession of the Palace. All these stages depict separation, transformation and incorporation as discussed by Arnold Van Gene Rites de passage.

(iv). The Chief’s Administrative Council in Lamurde

Officials who serve on the chief’s administrative council are from both the royal and the non-royal clans. They are appointed by the reigning chief and can be dismissed from office for wrongdoing or when another clan comes to power. The latter applies mostly to Zomye titled elders. Generally, offices connected with rituals and festivals are entrusted to Kabe, the custodians and servants to the chieftaincy. Let us first consider the chief’s administration at the outlying fiefs and villages.

(a). Offices held by Zomye

(i) Kpa Fwaye (The master of Fwaye): Fwaye are iron ornaments used in the arrest of criminals. This official performs general police duties including the investigation of incidents in the bush. Bush fires destroy harvested crops, which are left on the farms to dry. Unauthorized bush burning constitutes a serious offence punishable by heavy fines. Furthermore, during communal hunting, kpa fwaye assisted by other officials (see later) collect a few carcasses of animals as tribute and forward some of these to the palace. Kpa fwaye is regarded as the leader of all titled zomye, and upon his death, he is buried at Ndoko Zomon, the official burial hut of all titled zomye.

(ii). Ngurgoma (‘take it from him’); he collects tribute of cattle (jangali) from pastoral Fulani who graze within Bachama territory on behalf of the chief.

(iii). Ndwamatu-Ha-da-Nduron (Peer at the place called Nduron): He is the commander of the chief’s armed forces which consisted of a cavalry (ji-duwe) and an infantry (Ji-mbwara). The Bachama had neither a standing army nor a warrior class, both were not considered necessary since all able-bodied males were required to bear arms and participate in warfare. Special war drums (s. hubo duwe) are issued to village heads and fief holders by the chief upon appointment. War messages were transmitted on these drums in the past. This title holder, in the past, bore a sacred spear (kufe) and led the troops into battle.

(iv). Kpanate (master of the meat): He collects tribute from fishermen using the backswamp lakes, especially Goro Mbemun, Goro Bajen (Mbemun Zomon), Goro Tingno, Illapi, Wam, Gburuwa, Goro Bemti, Go Kutang (Tallemunagi), etc. during official fishing days set aside for the chief’s palace (kodo-home).

(v). Kpa Pudo (master of the big field): Is another investigator of fire incidences in those areas of the bush not covered by kpa fwaye.

(vi). Ndwamatu-Ha-da-Fwaye is the personal assistant of Kpa fwaye.

(vii). Kpanate-A-Sukore (the old Kpanate): this is an office reserved for former Kpanate who is considered too old for efficient performance of his duties. He represents the current holder in festivals and other official gatherings when the chief is expected to be in attendance.

Offices Held by Kabe (Non-Royal Clans)

(i) Nzopwato: his eponymous ancestor was met at Lamurde by the first wave of Bachama migration under Zaro embune, the twin brother who seceded and founded the Bachama chiefdom. Nzopwato receives muna-kpalto (returning the prophecy) from Jeke after the latter have returned from carrying ture (offering0 to the shrine of Nzeanzo at Fare. This prophecy (muna kpalto) relates to the condition of the world; for example, if famine, locust invasion, or any calamity, will befall the people, Nzeanzo will reveal this to Mbamto, the medium of the shrine. The medium informs Jeke who are the official messengers of the chief to the shrine at Fare. Messages received by Nzopwato from jeke are delivered to the chief during Buradou, the festival for the preparation for war. Nzopwato appoints Zeke to office as leader of the Jeke patriclan when the holder of the office dies.

(ii). Nzo-Kufe (Spear bearer); is the keeper of the original spear brought to Lamurde by Matiyavune. Nzo-kufe brings out the spear during important festivals, or formerly during time of war, when he handed it to the army commander.

(iii). Ndyewodi Tikka (the son from the House of Tikka); he breaks reeds-a method he uses for keeping the calendar of the annual festivals cycle. He carries ture (offerings) to Boso before important festivals take place. For this latter duty, he is assisted by Gura and Kpa Gure (below).

(iv). Nzofame (‘son of rain’): Fame is the Bwatiye name for “bole” (rain). This official is in charge of the sacred rain pot (mosuto). When there is a drought, he directs that black gowns be worn by all titled elders in Lamurde. Should there be abundance of rain; the same elders are directed to wear white gowns. The colours black and white symbolize the rain bearing clouds and non bearing clouds respectively. Whenever the chief leaves his Palace, Nzofame and Ndyewodyi Gongrong precede him to clear debris from his path.

(v). Ndyewodyi Gongron (‘the son of the house of Gongron’): He provided fresh fodder for the horses of the chief and plays an important role in the giving chief-elect a royal bath and administering oath at Yedi-kwatun during the installation ceremony.

(vi). Ndyewodyi Gosobon. Is the official in charge of the domestic affairs of the Palace and acts as the chief’s personal attendant. He sees to the comfort of guests at the Palace and supervises the burial of a chief at Ndoko-Hidon (the lone hut). He is assisted by three officials in his palace duties: (a). Dumkpa (‘bring out the calabash’); the chief waiter (b). Nzo-Dukshe (‘keeper of things’), the stores officer. He is in charge of provisions and items required for the installation of titleholders. (c). Nzo-Kuzoto (‘son of mat’), is the accomodation’s officer and provides lodgings for official visitors. In the past, Ndyewodyi Gosobon was the chief executioner of condemned criminals. Such people were led away to Tukoti (‘the place of darkness’), which is situated in the foothills of Bachama. For this particular duty, he was assisted by Nzo-hubo (‘son of a gourd’) whose praise chant (gboto) was said very early in the morning of the execution in front of the palace.

(vii). Nzomoto (‘close friend’). Is the head of Blacksmith clan in Lamurde and provides food and lodgings for those who come to seek political office from the chief. As indicated earlier, potential candidates for political offices buy their offices even though offices are hereditary. This is an aspect of achievement, for it brings about competition among members of the same patriclan. Such gifts for offices are offered to the chief, kabe and Jeke although the chief has the final say.

(viii). Gura: This official is in charge of important burials and is appointed to office by Nyewodyi Tika. Gura also carries ture (offering) to Bolki for important rituals as Mbwalto (okra) held in Lamurde. He is also held Lamurde. He is also responsible for the performance of the funeral duties. He is assisted by a female titleholder – Gurato, as well as a grave digger known as Kpa-Gure.

(ix). Kpa Duwe (‘master of the horse’). He assists Nyewodyi Gongrong providing fresh fodder for the chief’s horses. Kpa Dwe is in charge of the royal musicians and is the leader of the Bachama dancing troupe, Ji-wuro Kaduwe. The latter compose songs that sanction the behaviour of people they disapprove of, including the chief.

(x). Nzo-puke (‘son of the outer places’) provides lodgings for foreigners who come to Lamurde on official duties.

(xi). Nyewodyi Ngbakowon. He is in charge of the shrine of Ngbakowon where the Bachama golden stool is kept. In this shrine, the chief-elect remain for some days in seclusion from where he emerges to take possession of the Palace.

(xii). Kpa-Ngwaye (‘master of the waists’). He carries messages/directives of the chief to Kpana Rigangun (see below).

(xiii). Nwamato-A-Voti: He is the chief’s weapon carrier.

(xiv). Nzo-Nyiso Duwe (‘son of the horse’s tail). He holds the tail of the chief’s horse to prevent the animal flicking dust on the chief’s clothes.

(xv). Nyewodyi-Na-Zukati: This official is in charge of the Bwarambitikun, the deified wife of Zaro Dembune, the first Bachama King.

(xvi). Kpa-Mbwara (‘master of legs’). He is a general messenger, reputed to be tireless; hence someone who travels a lot is referred to as Kpa-mbwara.

Village Heads also collect tribute and adjudicate cases between wards (kwahe) within villages or between clans. Some of the cases include matrimonial disputes such as divorce or accusations of adultery. Cases from villages are either reported to fiefholders or direct to the chief. In the past, village heads made prompt reports on crop failure to the chief so as to be exempted from payments of tribute.

Another category of village heads come from priests of the major shrines located at Fare, Bolki. Byemti Gemuhn, Bolon and Nofarang. These priests also adjudicate cases and dispense justice and are an important court of appeal where the chief could refer unresolved cases to the gods. At the shrine, in the pre-colonial and early phase of the colonial administration, the accused and the accuser were subjected to a form of trial by ordeal to resolve accusations of theft, murder or witchcraft. The method used is called Zum-pulla (‘eating the spirit’). The guilty person was sent back to the chief’s court to be sentenced. Trial by ordeal was banned in the colonial period, but the gods are still expected to settle cases on behalf of the priests. Moreover, since farming is the main occupation of the Bachama, fertility of the soil is of prime importance in their minds, and because soil fertility depends on the correct performance of the priestly duties, this group of people wields lots of influence. Disobedience to the priests is believed to incur the wrath of the gods, which is discernable in the form of natural calamities including famine, locust invasion, outbreak of measles and smallpox, etc. Priests receive gifts of livestock, grain, cloth, etc. from people who seek their help. Traditionally, major shrines were sanctuaries where murderers could escape and nobody dared follow them. Such people were required to make offerings to the shrine annually. Wealth so accumulated would be distributed to relatives, friends and well wishers. In this way, the priests secure the goodwill of members of the society and increase their prestige as well. For further discussion on related aspects of the Bachama chieftaincy institution, see Stevens P. Jr. (1973:102-3; Dalli A.L. 1976:114-5).

CHIEFTAINCY AND LAND TENURE

Traditionally, land was neither bought nor sold in Bachama since land shortage was never heard of. The land of Bachama is entrusted to the chief at his installation ceremony, and he holds it on behalf of the dead, the living, and for the generations yet unborn. In other words, the Hama Bachama is a trustee; the land does not belong to him, therefore he cannot sell it. Villages have bush land (kikeh) and farmlands (gashe). The former was quite extensive and part of it was set aside for communal hunting. Farms are located within the boundaries of this (kikeh) and each villager in need of farmland would consult the village head. But when the people leave the village, their claims to farmland lapse, and ownership reverts to the village. The lakes of the back swamp are under the control of the chief and he alone appoints the middlemen in charge of fishing in lakes. The middlemen ensure that some of the days are set aside for fishing for the chief (kodo home); this means that the best catch from every participant would be voluntarily surrendered upon demand as tribute (shemto).

As indicated earlier, wards (kwahe) are inhabited by sectional patriclans; elders from these clans are familiar with the boundaries of land occupied by their fellow clansmen and those wishing to build are allocated portions. But if they fancy an area outside the control of their patriclans, permission to build must be obtained from the village head.

Village heads, as earlier indicated are appointed by the chief. They collect tribute on his behalf. This is one of the major way by which chieftaincy exerts control over land tenure. Communal hunting and fishing are organized with permission from the chief’s lieutenants. Land outside village boundaries come under direct control of the chief, nobody farms on these lands without prior permission form the chief. Middlemen may be allocated these lands for exploitation; they are not necessarily titled officers of the chief’s administration. They ensure that at least 505 of the tribute reaches the palace. As long as tribute continues to be paid, and the middlemen are not reported to be oppressive, they retain their positions for years. But they could be dismissed without warning by the chief, as potential candidates continuously report unfavourably their misdemeanor.

Finally, ward expansion in Lamurde is a recent phenomenon, perhaps dating back to the colonial period. Formerly, as one Zomye clan came to power, the clan of the previous chief would vacate the capital and take refuge in the villages far away from the headquarters so as to escape any possibility of reprisal from the clan in power. In the pre-colonial days, members belonging to members of the previous clan in power as punitive measures. With the end of hostilities following colonial rule, chiefs started carving out tracts of land at the periphery of the capital, where members of their clan could reside when their tenure in office was over.

Land sales are illegal by Bachama tradition; nevertheless, sales of land are common and occur in villages where land has a market value. However, to give legality to the transaction, both buyer and seller approach the village head to act as witness to the deal. For further discussion on Bachama land tenure see Meek, C.K 1932b, Dalli, A.L. 1976:126, and Karsfelt, N. 1981:29-30.

SUMMARY

The chief, at the conception level, recreated the installation ceremony, holds the society together and this is why that emphasis that he should be duly elected and installed. The chief settles disputes and is the highest human court of appeal I the past, he alone had the final say in matters of life and death.

The ritual calendar (Guda su kwale) is kept by the titleholder, Ndyewodyi Tikka at Lamurde. Performances of the first fruit ceremonies and other rituals depend on the accuracy in the keeping of this calendar. Ndyewodyi Tikka informs the chief when a ritual is due so that offerings are promptly sent to the shrine of the appropriate god. These gods are supposed to protect the chief and his subjects in matters of health and bountiful harvests. Offerings to the gods come from tribute collected by the chief’s subjects.

Looked at from another angle, the installation ceremony of a Bachama chief can be seen as a cognitive sacred sites relating to the history of the foundation of the Bachama polity are visited. The chief-elect is publicly authorized to rule Bachamaland and to collect tribute for the running of his administration. The public is there to witness this transfer of power and authority. In this sense the chieftaincy, religion, economy and ecology are all interlinked.11

CHRONOLOGY OF BACHAMA KINGSHIP

BITIPARAMO, ZARO DEMBUNE, MATIYAVUNE – 1704

He broke off from his twin brother, Zaro Kpalame at Demsa Mosu following dispute over succession to their father’s throne. He carted away all relevant royal paraphernalia and sacred ornaments and migrated with his followers and founded the Bachama kingdom with his first headquarters at Tingno. At Tingno, he married a second wife, before moving to make Bachama (Lamurde) his new headquarters.

At Bachama, Zaro Dembune, Bititparamo met Nzopwato with the first wave migration. For fear of elimination, Nzopwato climbed a tree and introduced himself as the man from above. Zaro Dembune also known as Matiyavune settled in Bachama (Lamurde) and bore four children namely; Nomupo, Nokodomun, Kowo, Magbullaron. The children of Matiyavune were trees he planted and flower that sprout on them.

MWAMO GWAMPA NZOKWAKLIKI – IMPANG CLAN

Before now, Zaro Dembune had adopted a son, whom he named Mwamo Gwampa, a lost boy found grazing with a herd of elephants during an elephant hunt south of Gyawana. When butchering their kill, the hunters noticed some movement under the elephant and were about to throw spears when they heard the cry of a boy. He was rescued and brought to the king who adopted him, and the spot where he was rescued became the ancestral home of his descendants; Dubo-wangun (“the mark of an elephant”).

At the time of the death of Zaro Dembune, Matiyavune’s children were not old enough to be given the throne. He therefore persuaded Bwarambitikum, that in the event of his death, the throne should be given to his adopted son, Mwamo Gwampa since none of his biological children was ripe for kingship. Consequently with his death, Bwarambitikum made a local brew and served the kingmakers with the objective of dulling their reasoning. On their enquiry, she named the brew sai vor kaba or vwe (beer). And under the influence of beer persuaded the kingmakers and contrived the selection of Mwamo Gwampa Nzokwakliki as the king that started the Impang clan.

Unfortunately, he could not make it to the palace as he was assassinated by the kabe at Tingn in Lamurde when he wanted to take another wife before entering the palace.

SUNGANOKADA – WADUKU CLAN

With the assassination of Mwamo Gwampa, the crisis of succession still persisted as none of Zaro Dembune’s children was old enough to mount the throne. The Kingmakers therefore opted to pick a regent from Kwagore “lakeside” at Gon.

On their way to Gon, Sunganokada overheard them discussing their mission. He quickly overtook them, rushed to the lakeside, feigning stomach upset asking Nzo-gon-to (“the man at Gon”) to find him some bitters (Duggune). Having sympathy for his friend, Nzo-Gon-to innocently went into the bush to get the bitters to cure his friend. Meanwhile, as the kingmakers approached, Sunganokada stretched himself on the man’s mat and the Kingmakers grabbed him, confusing him for the real man, and declared him king.

On arriving Bachama and taking possession of the palace, Sunganokada instructed his children that under no circumstance should they report his death to the Kingmakers, since they are not Zaro Dembune’s children; they stand the risk of losing the throne for good. They therefore contrived an arrangement that ensured seven different successions of the Waduku clan.

NZONZO – WADUKU CLAN

Not appointed by kingmakers. Usurped the throne through self-succession.

NZOZUMSHI TINGNO – WADUKU CLAN

Not appointed by the kingmakers. Usurped the throne through self-succession.

NAKARZO – WADUKU CLAN

Not appointed by the kingmakers. Usurped the throne through self-succession.

NGORON – WADUKU CLAN

Not appointed by the kingmakers. Usurped the throne through self-succession.

TUMBADI – WADUKU CLAN

NZOBALMATO – WADUKU

Nzobalmato is the 7th Waduku King that was not appointed by the Kingmakers and who like his brothers usurped the throne through self-succession. Nzobalmato was lured to Rigangun for a festival where the children of Zaro Dembune, Matiyavune have relocated. It was at Rigangun that Nzobalmato was overpowered and assassinated at Guleyi Gbomun to now pave way for the biological children of Zaro Dembune Matiyavune to have their taste of their heritage. Following the assassination of Nzobalmato, the children of Sunganokada became persona-non grata in Bachama land. They therefore moved out of Bachama speaking areas of the kingdom and settled south of Tingno in a place today called Waduku.

PRE-COLONIAL PERIOD AND CONTACT WITH EUROPEANS

Trade brought Europeans into contact with the Bachama and other ethnic groups along the Gongola and Benue rivers. In 1879, the German traveler, Flegel went up the Benue river and stopped at several Bachama and Mbula villages. The National African Company, which was later renamed Royal Niger Company in 1886, had been active in the Bachama area since 1883. In 1885 Adamawa became a scene of rivalry between England, France and Germany. It was partitioned by treaties between England and Germany in 1893, and between France and Germany in 1894. England acquired the portion that falls within Nigeria. In 1885, the Bachama King, Mangawa had concluded a treaty with the National African Company.12

In 1889, the British Government sent out a Commission led by Major Claude Macdonald and Captain A. F. Mockler-Ferryman to visit Royal Niger stations on the Niger and Benue Rivers. Macdonald’s report indicated that the then Bachama chief was a very old man. The main interest of the Royal Niger Company was to maintain friendly relations particularly with important tribes and chiefs through the payments of annual subsidies. These ranged, for example from sixty pounds (60) in Muri to thirty shillings to Mangawa, chief of Bachama. The payments were intended to keep the trade routes open by any means feasible and to prevent slave raiding. Subsequently, Numan became an important wooding station. Following a request for a factory by the Bachama, the Nigretia, one of the two new steel hulks which had been specially built for taking the ground in the dry season was allocated to the Bachama area in 1889. The other was sent upstream to Garua (Goruwe). Mangawa died in 1891 and was succeeded by Dongturong. The Bachama became agitated over the activities of the Hausa middlemen in their trade relations with the Company. In 1891 they attacked and destroyed the steel hulk in protest. The company, in reprisal, burnt down Numan the same year.

Bachama territory was visited by Lt. Mizon in 1891. During his second visit in 1893, he claimed to have signed a treaty with the Bachama. The same year the Bachama attacked a Company boat but were repelled in 1896 the company singed fresh treaties with the Bachama and Demsa granting them annual subsidies of 15 and 10 pounds respectively.

In the same year, Hewby engaged the village head of Mbula to be purveyor of wood to the company. This was the start of the relations between the Mbula and Royal Niger Company. Boima was the first Mbula to come to Numan and visit the representatives of the Royal Niger Company. He brought gifts and in return was given bags of salt and requested to collect as much wood as he could. This was carried out with precision; he collected a dump of wood from all Mbula villages. This pleased the representatives of the Niger Company that he gave Boima a flag and a letter and appointed him Chief of the Mbula. He became “Mai Takarda”. This title was retained in addition to that of Murum or Chief. Two years later (1896) Boima died and Safan, Boima’s understudy, was appointed chief. In 1904, Mr. Barclay, Resident, conferred the position of Headman on Safan. Consequenctly, the Mbula, who previously had loosely followed Nzodumso, Chief of Bachama, became a separate ethnic group. This new development led to the creation of the Mbula District. In 1906 Safan died and his brother Lina succeeded him. Lina was deposed and Usumanu, Boima’s son, was appointed.13

THE COLONIAL PERIOD, EUROPEAN EXPANSION AND CONQUESTS

The colonial history of the Bachama chiefdom can be linked to the fall of Yola after a fierce battle on 2nd September 1901 during which the Emir Zuberu was chased out of Yola and Bobo Ahmadu, his brother was appointed Emir.

From 1901 until the end of World War I, trade routes passing through Bachama territory were constantly blocked and traders attacked. The history of Bachamaland during the early phase of the colonial period altered between disturbances and patrols. Yola was made capital of British Adamawa in 1901, but an attempt to British administration into Bachama territory was resisted. Trade routes between Yola and Muri which passed through Bachamaland were blocked by the Bachama and Batta. Similarly, in the lower Gongola valley, the Bachama, Kanakuru and Lunguda created a barrier to trade and to communication, sufficient to cut off Yola from Muri and Gombe emirates. Consequently, a British patrol marched through the Bachama villages in 1901 to open up trade routes. In his monthly reports of March – December 1901, the Assistant Resident confirmed that fourteen Hausa traders were attacked by the people of Kwah, and that four traders were killed and all their merchandise taken. Kwah village was previously shelled by the steamers of the Yola expedition on the way down the river early in 1901.

In another incident, the Resident was informed that the Chief of Bachama had earlier instructed the village head of Gyawana to kill all traders passing to Kiri and Shelleng to collect gum; but that when the village head refused to comply, four Gyawana people were killed on the orders of the chief, and four horses were taken. The Resident; in his monthly report above, requested Lugard for patrol canoes to safeguard the Niger Company vessels and that if trading caravans were to be protected and the trade through the Bachama district to survive;

A company of the West African Frontier Force must operate for a month or so on both the river this season, and the sooner the better, any satisfactory operations against this tribe in the flood season are impossible. The case of these savages who have been chastised in a mild degree time after time these fifteen years is one of the many that uphold me in my firm conviction that any punishment inflicted on such tribes that does not carry with it severe loss of life, is largely a waste of energy and time not to be repeated.14

In response, the Bachama expedition of April 1902 arrived at Lamurde and deposed Nzodumso, chief of Bachama. Two years later, Nzodumso was reported to be causing trouble to the new Chief Zaro, and a British patrol kidnapped him to Yola. Following the capture of Nzodumso, the Bachama became settled and peaceful, the routes through their territory remain opened and safe for traders.15

In December, 1904, the former chief Nzodumso died in Yola.

THE REIGN OF CHIEF ZARO (1904 – 1910)

Chief Zaro started his reign as an ally of the British administration but after a few years he reported to be an obstructionist to progress, and his behaviour generally unsatisfactory. He extorted from his subjects and commandeered other men’s wives or young girls he fancied. Being an old man it would appear unlikely he would change much for the better, or be of much use to the administration. The Resident therefore recommended that Chief Zaro should be deposed.

Lamurde Patrol

The 3rd Resident in his letter No. 1072 of 29/09 reported on the Bachama and other truculent tribes. He stated that the Chief Zaro was a menace to the country and until he was deposed the Bachama tribe could not be ruled. He defied the Government and ordered the murder of Hausa traders. Mr. Dwyer asked that the Military detachment at Pella should be withdrawn and that the company should visit Lamurde, the capital of Bachama and deposes Zaro. Permission was granted and Mr. Dwyer, 3rd Resident, accompanied the patrol as Political Officer, and the medical officer, Dr. Ellis followed them shortly afterwards. They drove Zaro, who fled, and burnt his capital, Lamurde. The successor to Zaro, Kpafrato was installed. A few police were sent to support Kpafrato, and on Zaro’s returning to regain his throne, the police shot him dead. 16

The Monthly Report, Gongola District, March 1909 by S.H.P. Vereker on the Bachama indicated the deplorable attitude of Chief Zaro. He was asked to meet the Assistant Resident at a village half way from Numan to Lamurde. He sent his young son to say he was ill and could not meet him. “This I knew to be a lie as a private agent of mine knew that Zaro was actually traveling about in the bush at this actual time”. Further, this man had been told by Lamurde men that Zaro had state4d openly that he was not going to be bothered with any minor judge at Numan, that only the Resident himself would call him.

CHIEFS OF THE GONGOLA DIVISION June 17th 1909

Chief Zaro: Second Class chief of the Bachama pagans, residing in Lamurde, the capital town of the Bachama tribe.

Chief Mijibona: Third class Chief of the Kanakuru pagans, residing in Shelleng, the capital of the Kanakuru tribe.

Chief Joboi: Third Class chief of the Batta pagans, residing at Demsa capital town of the Batta tribe.

Chief Lina: Third Class chief of the Mbula pagans, residing at Mbula, capital town of the Mbula tribe.

The report on Gongola Division of June 30th 1909 confirmed that Zaro was summoned to Numan by the Resident Yola (and made to come against his wishes) he was severely reprimanded for his continued neglect to assist the administration, or in any way to do his duty as a second Class Chief. 17 It must be stated that the Second Class status of the Bachama Chieftaincy dated back to the reign of Chief Zaro (1904 – 1910). That this status was removed following the assassination of the Bachama chief by the administration. It is indeed pathetic that the Bachama chieftaincy is still at the second level in 2004, a position it had occupied 94 years previously.

The enforcement of Law and order amongst the Bachama during this phase of the colonial period was affected through political officers called District Officers (D.Os.). The District Officers ruled the Bachama directly and not through the chiefs, sometimes called ‘Indirect Rule’ in other parts of Northern Nigeria. The temporary absence of political officers from the Bachama area usually meant the suspension of trade, for traders were afraid to enter Bachama territory to collect gum and to sell their wares. However, with the arrival of a political officer, traders would return.

Tribute Collection

Bachama villages paid tribute to the chief in the form of gowns, livestock, guinea corn (sorghum), fish and fish sauce (bwe). There was a dispute between Zaro, Chief of Bachama (1904 – 10), and the Village Head of Opalo, over tribute. According to a previous arrangement the annual payable to the chief was valued at 35/-. When Zaro demanded more and this was not met, he deposed the village head. And a further mark of displeasure with the Opalo people for reporting the case to the Resident, Zaro placed an embargo over the fishing and hunting rights of Opalo village. The Resident reinstated the headman and restored the fishing and hunting rights of the village. He, however, cautioned them to continue their usual Bachama custom of paying a portion of their catch of fish to Zaro, after a big fishing day. The same procedure was adopted with regard to their hunting rights.

The payment of tribute to the colonial government was in the form of produce such as cotton and gum, both products being plentiful in the Bachama area. Gum trees were however, concentrated in three village areas, bare, Gyawana and Dubwangun, but distances between these villages and the Niger Company based at Gamadio and Numan were considerable. This would partially explain why Hausa middlemen initially prospered in the early phase of the gum trade. But with the construction of the Numan-Lamurde road in 1910, the gum trade was carried out directly with the company rather than through middlemen. It is difficult to ascertain if the Bachama from other villages ever participated in the trade.

The Colonial Government’s rationale for levying tribute on the Bachama was based on soil fertility, the presence of gum trees, the good fishing, along the Benue and Gongola rivers. But according to the Bachama religious ideas, soil fertility indicates the benevolence of the gods; therefore tribute collection based on such reasoning was injustice. Furthermore, the Bachama are not professional fishermen. Fishing is subsidiary occupation to farming among the Bachama, and is largely for subsistence.

Taxation

In the circular No. 1267/1909 of the 17th June, 1909, the Assistance Resident hinted that taxation was scheduled for introduction among the Bachama in 1909/10 at the rate of two shillings per compound, or about a pence per adult male and female. Taxation was un-welcomed throughout Bachama villages, and reactions against its imposition varied from one village to another. Some villages refused to pay and faced the consequences; others punctually vacated their villages to evade the tax collectors, some remained and attacked these tax collectors. In 1917 for example, Kpafrato, Chief of Bachama was assaulted and driven out of Waduku Village when he came to demand a balance of one pound, one shilling. In act of solidarity, the colonial administration organized a patrol under Major Brodie and Dr. Porteegus W.A.M.S. They arrived Numan on November 11th, 1917 and left for Lamurde the following day. On November 13th they arrived Gyawana, on the 16th the patrol reached Rigangun where those who made trouble to Kpafrato were arrested, tried and punished by the native court; in addition, three compounds of these adherents to Zaro were destroyed. On 17th they marched to Waduku and found that it had been deserted. On the 18th, the whole village was destroyed. On the 19th, the patrol arrived Kwa and found it deserted; they followed the inhabitants into the bush on the 21st. At this juncture, the village head promised to collect the remaining balance of 7 pounds.

The force retracted its steps to Vorkadan and arrived on the 23rd then Kiri and Shelleng District on 25th. Finally, they reached Guyuk on 26th. 19

Kpafrato (1910 – 1921)

Despite the backing he received from the colonial administration in 1910, his report was simply deplorable:

Kpafrato, chief of Bachama proved very lazy and very incompetent, nor does he appear to try and take the Lead enough amongst the Bachama who are always

Inclined to be truculent and independent and require a firm hand.

By 1912, there was no improvement in the reports.

Kpafrato the 3rd chief will in time, in my opinion do well, he is lacking in initiative, but he is gradually being looked up to and feared as the District Head

And has now some authority among the people.

The people are lazy and drunken and require a firm handling. 20

The most comprehensive report came from the Resident. Yola Province to Secretary Northern Province Kaduna seeking the approval for the following:

Kpafrato 3rd class chief and Headman of the Bachama tribe Numan Division has ceased to be of use. He is Not only too old – 75 years of age and appointed in

1910 – But the Bachama themselves now distrust him and he undoubtedly obstructs our rule whenever the opportunity arises to do so. The following are some of the more recent confidential reports on this man.

MR. WEBSTER – Lazy and has to be driven – a bully 1915.

CAPT. BRACKENBURY – Requires constant attention 1917.

MR. VEREKER – An obstructionist and utterly untrustworthy –

1920 It is proposed to retire Kpafrato and give him a Pension of 2 pounds a month. His salaries have been 9 pounds a month.

But it would be unwise to allow him remain within Bachama territory as he will undoubtedly, through Intrigue cause trouble. I am assured that, he will certainly lose his pension through misconduct. As there would be least chance of this under the immediate Supervision of the District Officer at Numan. I recommend

That he be made to reside there.

His successor will be elected by the majority vote of the Tribe and if found to be a likely man will be tried for Three months or so before being given the position.21

The colonial administration had thought the choice of the Bachama would fall on Mbuldi who was then about the most likely man from their point of view to make a better chief. There were four candidates:

Mbuldi: The most likely choice, he was the son of the incumbent Chief’s brother. He was a very popular person among the Bachama and had a large following. He was a Police constable and a Wakili for the Bachama tribe.

Kpafrato’s Son: a rogue and requires constant watching and is detested by the tribe.

Kpana: Too old and would be no improvement on the incumbent chief.

Mbi: A good man but it was considered that being a convert to Christianity, his following would be very large.

Mbi (1921 – 1941)

At mass meeting of the Bachama at Lamurde, Mbi was unanimously chosen chief and was accordingly installed in office on 16th January 1921. The Resident Yola in his application for confirmation of the appointment of Mbi as chief of Bachama noted:

Mbi was selected by popular vote and is carrying out his Duties in a satisfactory manner. I recommend that his Appointment be confirmed. The District Officer, Captain Brackenbury reports that Mbi’s influence among his tribe Appears to be good and gaining strength. He has an Extremely difficult position to fill owing to the fact that he is a Christian, and the office of the chief among the Bachama involves to some extent that of Priest in a sense as well. But I understand that he has delegated His Pagan religious duties to another.

It became clear to Bachama King Makers that the colonial government would only work successfully with a chief they approved. Mbi was their immediate example who was a product of the Mission school, a school teacher and a Christian. To crown it all, the chief broke their chieftaincy tradition when he moved his capital from Lamurde to Numan in 1921. By so doing he left the elders with religious rituals completely. But following in the footsteps of his predecessors. Mbi fell out with the colonial adminstration23 On June 18th, 1941 the chief left by canoe to Yola Hospital and died on June 29th, 1941. The following day, 30th June, 1941 a Telegram was dispatched:

Executive Numan

Much regret to inform you Sarkin Bachama died in Hospital

here of a stroke yesterday and convey my sympathy and

Condolences to relatives and council.

Resident.

Ngbale (1941 – 1967)

The following information is derived from a letter from the District Officer, Numan to the Resident, Adamawa Province:

On the death of Mbi, late Sarkin Bachama, I called in the welders of the Hamlet of Hadio and asked them the procedure adopted according to Bachama custom for the selection of a new chief. I was informed that the selection board consisted of the following eight persons:

NAME TITLE VILLAGE

Vunkai Zeke Hadio

Gumanayele Zeke Hadio

Masun Nzokwandokai Hadio

Filo Nzopwato Lamurde

Hinda Ndyewodyi Tikka Lamurde

Dikodimma Ndyewodyi Tikka Lamurde

Kaleno Nzofame Lamurde

Detiwa Ndyewodyi Gosobon Lamurde

There are two holders of the title Zeke, the past and the present holder, and for the purposes of the selection of a chief both are present although Vunkai, the past holder, has now ceased his executive duties. Again, there are two holders of the title Ndyewodyi Tikka. Hinda being the senior and Dikodimma his assistant. The title holders from Lamurde are all ward heads with the exception of Dikodimma.

I pointed out that from records available, the chief of the tribe were selected in turn from two Royal families.

I asked the names of these families and was told that they were Nomupo and Nokodomun but that this procedure had only been adopted since the advent of the British administration. There were six houses from which chiefs were chosen in the past and the selection stated that if they were now allowed to choose according to their custom, they would choose somebody from one of the other four houses. The names of the remaining houses are Kowo, Magbullaron, Waduku and Impang. I replied that I did not consider that there would be any objection to this procedure provided that the method of selection was settled now once and for all.

The next step was to obtain the genealogical trees of these six ruling families and representatives from the families were called into Numan for the purpose. At the suggestion of the Sarkin Demsa and Murum Mbula, the board of selectors was present when the elders of the house were being interrogated. After some considerable time, a small family tree of one of the houses was drawn up but it was found that it did not contain the names of two or three of the previous chiefs. It was obvious that the elders did not understand what was required of them, so different tactics had to be employed. It was decided that they should give me the names of those of their house that were living and thus, I thought I might be able to work backwards. After having written 72 names, I enquired if all the six houses were of this size. I was told that this house had not yet finished their list and that all the houses were about the same size. The idea of genealogical trees therefore, had to be abandoned and since the scribe was able to write down their names quickly than myself. I arranged for him to make me a list of each house and the names of those who were eligible for the chieftainship. A few days later, he produced a list of 846 names saying that there were still many more but that he considered it was a waste of paper writing them down. This I agreed. None of these people had any executive post so there was no chance of choosing somebody with previous experience in administration.

The only method left now was to see the selection board and discuss the position with them. I pointed out that I had hoped to find somebody who was known to the administration and who was acquainted with the methods of British administration but that was not possible. It was left therefore to them to choose somebody whom they knew to be popular and if possible, of industrious habits. They replied that they had discussed all this between themselves and that they were unanimously in favour of a man from the house of Kowo by name Ngbale who lived at Rigangun. They said that he was popular with the people and was an industrious farmer. His father, Ali had held the title of Ngurguma. This used to be the title given by the chief of Bachama to the person responsible for collecting toll fro the Fulani cattle owners grazing in the District. The position was one of importance and is said to have been well held by Ali who was popular all over the District. His son is said to be following in his father’s footsteps.

I have seen Ngbale and spoke to him about farming and cattle. He appears a quite and inoffensive man of about 35 years. He is short of stature and not of imposing appearance. I am informed by the selection board that he is capable of looking after their tsafi rights. I therefore submit his name for consideration.

It would not be out of place here to place on record

The order of the houses from which the chiefs are chosen.

They are Nomupo, Nokodomun, Kowo, Magbullaron, Waduku,

Impang. If by chance there is no suitable candidate from the

House next on the list, a man from where no suitable candidate

Was obtainable has to wait its turn round again.

In September, 1941 the appointment for Ngbale was approved. The reign of Ngbale was relatively more peaceful than the reigns of his predecessors. The major incidence which would have cost Ngbale his throne was the issue about Bachama District Headquarters dated June 3rd – 5th, 1946. I was suggested that the chief of Bachama reside at Lamurde at least for 8 months of the year on the pretext that public buildings such as court, District Office etc. would be erected. When Ngbale disclosed the plan to the king makers in Lamurde, they advised him to resist; but if he must leave Numan, he should not go to Lamurde. They would be grateful if he moved ahead to Rigangun where they picked him for the chieftaincy. Ngbale refused to leave Numan. Coincidentally, the District Officer’s letter to the Resident stated:

Mr. Delves-Broughton minuted as a handing over note that he does not think a move of the Bachama District Headquarters to Lamurde practical politics at present and from what I have seen, I entirely agree. To reoriented the Bachama tribal and economic focus back to their foothills in Lamurde when Numan and

The Benue seems their chief hope of social and economic progress appears tome not in the best interest of their economic future. The Bachama are more vigorous and their numbers are more than twice that of the Batta and Mbula tribes. Moreover, Sarkin Bachama himself is Strongly opposed to moving his headquarters to Lamurde. Closer contact and administration of the Pire and hill people can be achieved. I suggest, by more touring in the area without the necessity of moving the tribal headquarters to live near them.

Ngbale was the first Bachama chief in the Northern House of Chiefs Kaduna, during his reign, Nigeria achieved independence and was fighting a civil a civil war in 1967 when he died.

Jaman, Muregursuson (1968 – 1975)

He was appointed to office by Kabe (King Makers). His short reign saw the beginning of industrialization in Bachamaland in the form of the Savannah Sugar Company Limited the only industrial establishment of its type in the then Gongola State.

Reverend Wilberforce Myahwegi (1975 – May 20th, 1994)

He was appointed to office by Kabe, and is the second Christian Chief of Bachama, after Mbi (1921 – 41) as well as the second Bachama chief to be issued the 2nd Class Staff of office, after Zaro (1904 – 1910). During his reign, 9 Districts were created in the Kingdom.

Freddy Sodity Bongo – Takude – IMPANG

Appointed by Kabe (Kingmakers) in 1994. During his reign, Lamurde Local Government Area was created giving the chiefdom two local governments. The Numan Traditional Council was splitted to give each chiefdom its own traditional council. Consequently, the emergence of Bachama Traditional Council, and Savannah Sugar Company Limited was privatized. He was generally perceived as weak ruler who ceded too much authority to his wife, the Mbamto, whose interference in governance derailed his reign. His reign was characterized by allegations of highhandedness and marked by ethnic and religious disturbances that led to his eventual deposition in 2004.

Asaph Zadok – Goro Ngakye Kuzo Vudeto KOWO CLAN – 2004

CHRISTIAN MISSIONS AND CHANGE IN BACHAMA SOCIETY

Christian Missionaries arrived in Bachama society during the colonial period. The Ag. Resident G. W. Webester in Report No. 81 of 30th September, 1913 stated that Dr. Bronnum of the Sudan United Mission arrived here on the 29th of September with a view to establishing a Mission at Numan. I have not yet received any definite proposals from him. Later in the year the Ag. Resident in his report No. 31/12/1913 on Mission stated:

Dr. Bronnum of the Sudan United Mission is living in temporary quarters at Numan pending the sanction of a site for a Mission station. Mr. Ryan reports that the natives are all going to him for medical treatment.

Pending His Excellency’s decision he is of course doing no school or Missionary work.

The Missionaries introduced Christianity. Western education, medical services and new crops into Bachamaland. The colonial period opened new economic opportunities and exerted economic influence on the Bachama people through the introduction and diversification of new crops and the technology of their cultivation. The Bachama economy became more cash oriented, and labour became a major constraint. The introduction of cash crops has contributed to the changing labour relations and supply in the economy of the Bachama area. Groundnuts were first introduced as cash crop in 1943, but soon declined due to depredation by monkeys and pigs. The mixed farming programme was extended to the Bachama area in 1951, and farmers obtained loans from the government and purchased ploughs and oxen. Cotton was re-introduced as a cash crop in the Bachama area the same year. Throughout the decade 1951 – 1961, cotton farmers increased their acreage, and cotton became the leading export crop from the Bachama area. The owners of ox-ploughs were willing to be hired to cultivate fields and be paid on a task basis for cash. The prices paid for cotton were considered fair by Bachama farmers in comparison to the domestic prices paid for foodstuffs. With the completion of the Gombe-Numan portion of the road from Jos to Yola, cotton could be evacuated as a cash crop from Bachama society, mainly due to better prices paid for food crops in the domestic market place.

The introduction of the hiring scheme in 1959 is the most important agricultural development programme brought into Bachama society. The tractor hiring scheme has simplified labour relations. Farmers are only required to pay an amount equivalent to the number of acres to be cultivated. Farmers wait for several months every year for the tractor to arrive. Initially, tractor services were mostly used for cotton production, but when prices of cotton depreciated, Bachama farmers from the bawe environment Upland, shifted to the cultivation of rice, Rigangun village, for example, used its Kampani organization for labour supply on members’ farms. Zangye farmers (Riverbank), although rejecting cotton as a cash crop, utilized their traditional labour relations through family and beer farming in cash during the dry season. Traditional tools such as the hoe, machete and dibble are used in the technique of the dry season cultivation (shepshe) is derived from the neighbouring ethnic groups. Reciprocity in labour relations is more meaningful amongst Zangye farmers than is the case amongst the Bawe people.

A contributory factor in the shortage of labour supply was the civil war (1967 – 1970) when thousands of able-bodied Bachama males enlisted into the armed forces. Their departure alerted the pattern of labour relations and supply in Bachama society. Traditionally, success in beer farming (hau vwe) was judged by attendances, but during the civil war, attendances declined and hired labour became more expensive. Head porterage could no longer be relied upon for the evacuation of farm produce to granaries: fortunately, pick-up vans and tipper Lorries were available for hire. Those with relations in the armed forces received cash remittances in the form of allotments during the civil war. Some farmers from the Bachama area utilized part of the money from this source to pay for labour.

The last decade (1970 – 80) has witnessed an increased activity by the Savannah Sugar Company with regard to land acquisition. Land has a monetary value in villages where the employees of the Company reside, and this is contrary to the general land tenure system of the Bachama. As can be deduced, the relationship between Zomye (royal clans) Kabe (non-royal clans) and their environment are usefully discussed within the context of their history of their history. The Bachama people’s conception of their social and natural environment is re-enacted at the installation of their chief, bringing together an interaction between the territorial and religious structure of the society embodied in the role of the chief. The chieftaincy is viewed by the Bachama as the symbol of their unity and of their existence. They clearly state that if the chieftaincy should disintegrate, the Bachama nation disintegrates. Moreover, the chief is the trustee of the Bachama natural environment and holds Bachamaland on behalf of the dead, the living and the future generations.

BACHAMA CHIEFS AS CEREMONIAL HEADS IN COLONIAL AND POST INDEPENDENCE PERIODS

Clashes with the colonial government have serious consequences on Bachama chieftaincy. Between 1900 and 1921, out of the three chiefs who reigned, one was shot dead while the other two were deposed. These misfortunes led to a loss of power on the part of subsequent chiefs.

Formerly, in legal matters, the chief was the highest court of appeal and he alone could decide between matters of life and death of his subjects. But the colonial government usurped the chief’s power and tried all criminal cases. Moreover, it was impossible for the chief to declare war against rebellious village head in his domain as was customary, or wage war against an external enemy. Because warfare was abolished by the government, another important and exciting aspect of the chief’s power was lost.

One of the major attractions of the chieftaincy institution in Bachama society has been the material benefits. When payments of tribute were abolished and hunting of big game was declared illegal, the privileged position of chiefs was curtailed. As a form of compensation, chiefs were placed on salaries in modern currency. But the salaries are inadequate in meeting expenses of the palace. Meek C. K. (913ib:47) has correctly observed.

The necessities of the royal household are met by gifts of corn from every farmer according to his ability. It might be considered that under present conditions, as a chief receives a regular salary, the presentation of corn to the chief should be discouraged, that would in my opinion, be taking a very short view. The gifts of corn are in no sense an exaction, they are free gifts of the people to the chief as expression of the loyalty they feel, and as a way of payment for services rendered – service which are not always obvious to the European.